At the age of 20, after two earlier visits, Puerto Rican Juan Tizol arrived in New York as a stowaway--to make his living as a musician. His greatest asset—he lost all his money and his valve trombone when gambling on the journey over—was his thorough training in classical music. Throughout his long career he maintained a classical approach while adapting to the jazz idiom enough to achieve great success. After long tenures with Duke Ellington, Harry James and Nelson Riddle, he left behind a rich legacy of compositions and recorded music.

Tizol didn’t stay long in New York, leaving for Washington, DC, to obtain regular employment in the pit orchestra of the Howard Theater. When the Howard Theater closed four years later, he freelanced for several years. It was through gigging in the capital city that Tizol became friends with the man who was to be his boss for 14 years—Duke Ellington. Duke was fronting several bands at the time, but he didn’t hire Tizol until 1929 when they had both moved to New York.

The Ellington Years

Ellington was impressed by the trombonist’s musicianship and was not deterred by his strong classical bent. Ellington knew Tizol wasn’t an improviser: “He won’t ad lib.” (Richard O. Boyer, “The Hot Bach,” New Yorker, 1944) but he saw plenty of other values: an ability to sight-read, copying skills with written music, a his pure sound on his instrument, and an ability to play difficult parts with his valve trombone. Ellington’s success in the late 1920s had made him extremely busy—he had demanding gigs at the Cotton Club and with the Ziegfield Follies—so he badly needed a skilled copyist to help with producing band scores for his compositions. According to Lawrence (Duke Ellington and His World,144), “Ellington would write in concert (the notes off the piano) and give Tizol the score, and Tizol would transcribe the parts [for each band member].”

Tizol’s duties expanded in the early 1930s. He contributed to the Ellington sound in his “extractor” role, sometimes supervised rehearsals, and eventually provided original compositions—all this while filling an important role as a player. Tizol was Ellington’s right-hand man for most of the 1930s, until Billy Strayhorn joined the Ellington organization and gradually too over Tizol’s role.

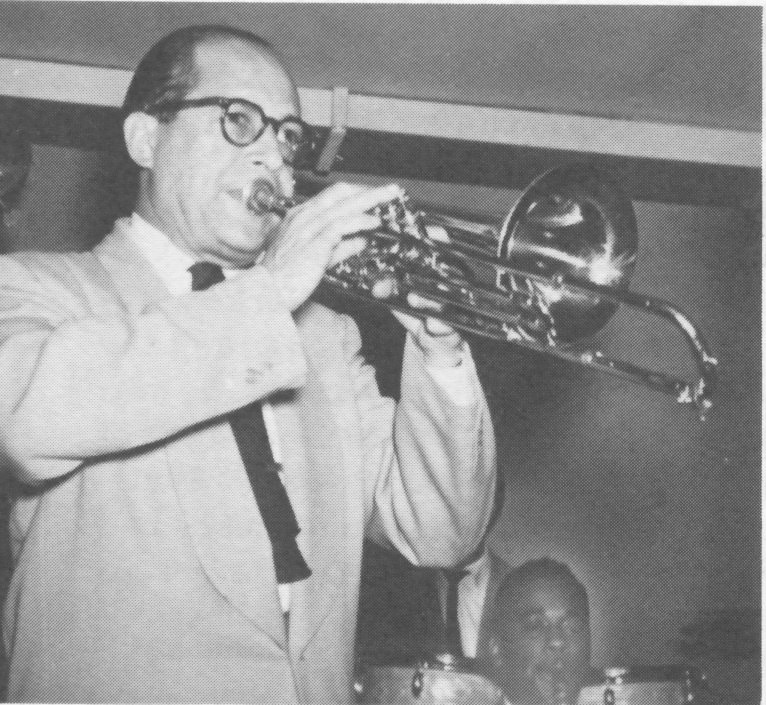

Tizol (with glasses below) first recorded with Ellington on September 29, 1929. In the next 18 months he played on the first recordings of two of Ellington’s most successful compositions: Mood Indigo and Rockin’ in Rhythm. Initially, Tizol’s presence as a second trombonist can be detected mainly in the ensemble playing, but he can be heard playing in a short duet-solo with Joe Nanton on “Admiration” (1930). Once Tizol joined, the band’s tonalities are richer. An early example is “Creole Rhapsody” (11 June, 1931). Ellington’s arrangements often utilized Tizol’s speed on his C valve trombone; he sometimes played with the saxophone or trumpets sections. Stanley Dance wrote that” Tizol made a greater contribution to the ensemble than has perhaps been generally realised.” (Sleeve notes, Duke Ellington, Rockin’ in Rhythm, Vol. 3)

His soloing came later. On “Caravan” he solos the melody for the first minute, sticking closely to the melody and exhibiting a very fast vibrato. A film of a faultless performance of this number can been seen on YouTube. Ellington used Tizol in a similar introductory way on other Tizol compositions: “Jubilesta” (1937), “Lost in Meditation” (1938), “Pyramid” (1938). On “Flaming Sword “(1940) Tizol gets a short solo that sounds written. And on “Ko-Ko” (1940), one of Ellington’s finest recordings, Tizol solos the riff theme. Gunter Schuller sees Tizol’s instrument ideal for this number: “The leathery, slithery sound of Tizol’s valve trombone makes it the non-pareil instrument for the occasion. A saxophone would have sounded ordinary, and on the slide-trombone this riff and that register and that tempo is virtually unplayable.” (The Swing Era,116) Early in the 1940s Duke again featured Tizol carrying the melody in two more important recordings: “Conga Brava” and “Bakiff.”

Composer

With the exception of “Admiration” (1930), Tizol did not emerge as a composer until “Moonlight Fiesta” (1935). His most celebrated composition, “Caravan,” came soon after (1936). Tizol will be remembered for this song above all else. It became increasingly popular over the years. Notable versions have been recorded by Art Tatum, Thelonious Monk, Wes Montgomery, Wynton Marsalis and Michel Camilo. “Caravan” was in the Ellington songbook until the end. And to think that Tizol sold the rights to Irving Mills for $25!

Following “Caravan,” a steady flow of Tizol compositions appeared on Ellington recordings—all within five years: “Jubilesta” (1937), “Lost in Meditation” (1938), “Pyramid” (1938), “Gypsy Without a Song” (1938), “Conga Brava” (1940), “Flaming Sword” (1940), “Bakiff” (1941), “Moon Over Cuba” (1941), and “Perdido” (1942).

These compositions, with the exception of “Perdido” and “Flaming Sword,” all had what is generally called a Latin flavour. I would rather use the adjective Moorish, which is more appropriate, especially for “Pyramid,” “Gypsy Without a Song” and “Bakiff.” Tizol’s musical education in Puerto Rico was heavily influenced by the Spanish, who had occupied the island until 1899. And of course, Spain was heavily influenced by the Moors, who controlled the Iberian peninsular from 711 to 1492. Many of Tizol’s compositions have a haunting meditative and melancholy feeling that some call middle-eastern or Arabic as well as Latin. Tizol’s moorish flavour is less rhythmic than the Spanish or Latin flavour. Ellington was attracted to this mood, just as he was to the more Latin rhythms like the conga.

“Perdido,” Tizol’s other very successful composition does not have this Moorish flavour. It is a very simple tune and easy to play. It was quickly taken up by the bebop players of the 1940s, like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, quickly becoming a jazz standard. It never left the Ellington concert book.

After Ellington

In the early 1940s, Tizol was less featured as a composer and as a soloist. This, as well as the growing status of Billy Strayhorn as Duke’s right-hand man, may have contributed his departure from Ellington after 15 years in 1944. The official reason for his departure was to stop travelling and settle with his wife in California. However, Tizol went straight to Woody Herman’s band, which travelled a lot and was based on the East Coast. Soon after he switched to LA-based Harry James (See below on left with Perry Como and Tizol) and stayed with him until 1951.

Tizol’s role with Harry James and His Music Makers as similar to his role with Ellington—adviser, composer, straight-melody soloist, and second-in-command. Tizol soloed for James on many of his own compositions: “Joe Blow,” “By the Shalimar,” “Zambu” and “Moonlight Fiesta.”

Despite his wonderful working relationship with James, Tizol left him in 1951 to return to Ellington for the next two years. “Harry was mad at me,” Tizol recalled. (Smithsonian Interview, 1978). This move, known as “the Great James Robbery,” –Tizol took Louie Bellson and Willie Smith with him as well, in a move that shook the music world. At the time Ellington was having difficulty keeping his band together after the loss of Hodges, Brown and Greer. Tizol came to the rescue, clearly feeling his loyalty to Ellington outweighed his loyalty to James. Ellington remembers that loyalty in his memoirs: He was in LA just after losing his three longtime players. Tizol invited Duke to dinner just after Duke lost his three star musicians. Tizol told him, “All you’ve got to do is to say the word, and take Louis Bellson, Willie Smith and me, and we’ll leave Harry James and come with you.” (Music is My Mistress, 56)

During Tizol’s second tenure with Ellington (1951-3), the band was rejuvenated. It is interesting, in view of Tizol’s strong Californian ties, that the Ellington band carried out three major West Coast tours while Tizol was with Duke for this second time. In 1951, Tizol also played with The Coronets, the Ellington band under another name. Tizol can be heard on a reprise of “Moonlight Fiesta.” Then in the fall of 1953 Tizol returned to Harry James. There was no fuss this time; probably Tizol had done his bit for Ellington and could now return to James.

The rest of his working life was spent in California. As a session-man, he was always working. Apart from his duties with James, he also did work with Nelson Riddle, Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole and Louis Bellson. He played on many of the celebrated albums Sinatra recorded with Riddle. He was also in Sinatra’s band for his television show (for more than a year). He also spent a year with Nat King Cole and is featured on three numbers from Cole’s Midnight Sessionalbum. As usual, he doesn’t improvise. “Blame It on My Youth” is a fine example of his muted trombone playing—with a little less vibrato than in his earlier days.

Conclusion

Certainly the most important period of Tizol’s career was his first tenure with Ellington. He contributed mainly as a trombone player and a composer. But his assistance to Ellington as an extractor and as a second-in-command might have been just as significant. There is no way of telling. As a player, albeit classical in approach, he contributed a lot to jazz as a trailblazer for his instrument and as a supreme technician. His clean and accurate style has been described in Ellington’s Bones by Kurt Dietrich as “straightforward with little inflection added to the line, but colored by his burnished tone and intense vibration.” (64) John Hammond, who was unsympathetic to Ellington’s music, nevertheless appreciated Tizol’s playing when attending Ellington’s first Carnegie Hall concert in 1943: “Tizol’s ‘Bakiff’ is little more than dressed up movie music, but the composer played magnificently.” (“Is the Duke Deserting Jazz? Jazz 1/8, 1943)

Tizol’s classical music approach benefitted and enriched jazz in many ways. It took a musical genius, Duke Ellington, to see that a “legit” musician could still contribute to jazz even if he stayed true to his classical training. And Tizol always did stay true to his classical roots. He told Richard O. Boyer in 1943: “If there was any room in legit, I’d still go back to legit…. I don’t feel the pop tunes, but I feel La Gioconda and La Bohème. I like pure romantic flavour, I can feel that better.” (New Yorker, 1944)

3 Comments